Some marketers might advise you to embrace the competitive component of marketing a business and take a more combative stance that utilises elements of enemy-centric marketing.

However, we would like to go one step further; because we believe that the act of defining an enemy should not simply supplement your marketing efforts, but define them.

There is untapped power in enemy-centric marketing. And to make our case, we are going to:

- Examine the history of enemy-centric persuasion

- Provide an outline of how you can devise successful enemy-centric branding for your business

- And, take a look at some examples to inspire you

Isn’t Enemy-Centric Marketing Antagonistic & Disreputable?

Although we believe that the nature of marketing should be combative, we also acknowledge that many businesses are understandably resistant to the seemingly antagonistic aspects of this position (or at least claim to be).

In this article, we will argue that “marketing warfare” does not necessarily need to demoralise or antagonise the competition in order to be enemy-centric.

In this article, we will argue that “marketing warfare” does not necessarily need to demoralise or antagonise the competition in order to be enemy-centric.

And we will also show you how to achieve a combative stance and benefit from enemy-centric marketing without compromising your values.

Isn’t “Conditioning” Buyers Unethical?

As Nadeem Yousaf puts it in his blog NadTalk, “marketing means conditioning the customers’ response. All firms consciously or unconsciously strive to condition their potential customers and the market”.

This is an important point for any readers currently raising their eyebrows.

We get it. “Conditioning” doesn’t exactly scream authenticity and trustworthiness. Just the opposite. It’s practically synonymous with manipulation and brainwashing; terms no principled businessperson or marketer wants to engage with anymore than necessary.

But as Yousaf rightly points out, all businesses strive to condition their customers—consciously or unconsciously. Whether you do this through genuine or disingenuous means is the real measure of your values.

Still not put at ease? Here’s an example.

Let’s say you’ve engaged the services of a reputable product photographer for your brand. This particular photographer takes bright, colourful pictures of your product. You know your customers will respond well to these images, because they elicit feelings of positivity. Though no one could argue that this is in any way manipulative or disingenuous, the fact remains that conditioning has played a part in the aesthetic you chose for those images.

In fact, we could argue that at the level of the individual, the mere use of social media is a form of conditioning. There is a reason we choose images that show our best features and subdue the things we like least about ourselves. After all, that’s what filters are for. We are creating a version of ourselves that isn’t wholly truthful to condition our audience’s view of us.

Businesses, politicians and enterprises all act in exactly the same way, but at scale. To expect any less would be naive.

Therefore, understanding the role that behavioural psychology plays in consumer marketing isn’t unethical; it’s realistic. To ignore its role would be much like swinging a bat while in a blindfold and pretending you’re not swinging a bat at all.

The History of Using An Enemy To Condition People

We’ve been using the power of defining an enemy for hundreds of years. And the most potent example of this is propaganda.

Here’s an example:

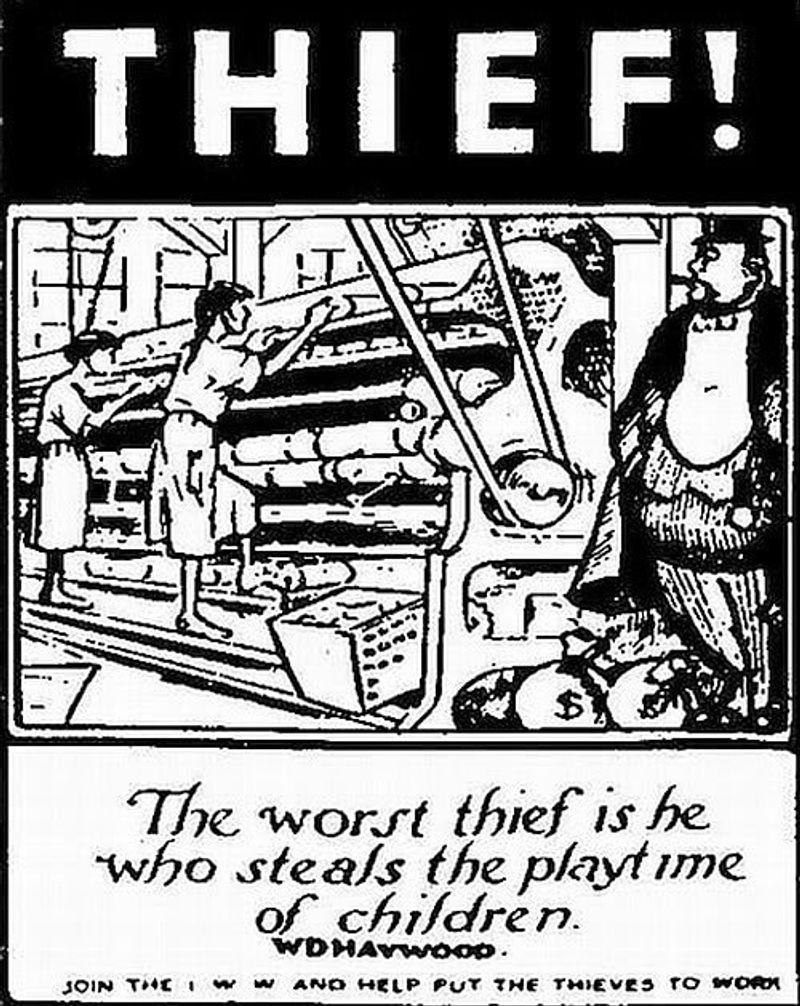

This poster from 1912 depicts the exploitation of children in textile mills. And it is a prime example of explicit enemy definition in a campaign. This image was released by the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W) and encourages its audience to join them.

In the image, a large, wealthy man watches the children work, surrounded by bags of money. The call to action at the bottom of the poster readers, “Join the IWW and help put the thieves to work”.

Why does this particular propaganda example work?

Though this poster could have served a similar function by solely featuring the exploitation of children as labourers, the creators chose to establish an enemy. In this case, the wealthy individuals benefiting from child labour. The title of the poster reads “THIEF!”, a bold accusation instead of a call for aid.

By emphasising the guilt of the perpetrator over the plight of the children, the creators of this poster have chosen to incite anger over empathy. Which begs the question, which is more effective at motivating action?

According to an article published on Spring, anger is “a kind of positive energy and a powerful motivating force. Research has shown that anger can make us push on towards our goals in the face of problems and barriers.”

Empathy, on the other hand, has been proven to have numerous limitations, such as “the desire to avoid emotional exhaustion”. In a post titled Motivation and the Limitations of Empathy, researchers acknowledge that the drive to avoid emotional exhaustion may cause people to avoid empathy and could even produce compassion collapse.

Their study found that “people have a strong preference to avoid choosing empathy for others, and that this is associated with perceptions of empathy as effortful, negative, and inefficacious”.

You may well recognise the differences in motivational drive between empathy and anger in your own life. While empathy can often evoke feelings of powerlessness and sadness (both demotivating forces), anger is the emotion that powers action, such as protests.

Moreover, anger is, of course, a byproduct of opposition and conflict. Which is why anger is so often a motivator in enemy-centric campaigns—particularly political campaigns.

Are Marketing And Propaganda Two Sides Of The Same Coin?

In his book Propaganda, Edward Bernays writes:

In his book Propaganda, Edward Bernays writes:

It was not until 1915 that governments first systematically deployed the entire range of modern media to rouse their populations to fanatical assent. Here was an extraordinary state accomplishment: mass enthusiasm at the prospect of a global brawl that otherwise would justify those very masses, and that shattered most of those who actually took part in it.

As Bernays points out, WW1 propaganda was a means to incite “mass enthusiasm” and “fanatical assent”.

At first glance the strength of these terms may seem a little too dramatic for consumer attitudes. But we need look no further than Apple’s fanbase for similar levels of enthusiasm and fanaticism.

In an article featured on Fast Company, the author refers to a long-running joke about Apple consumers and their “fanboyism” reaching a “cult-like status”. The author writes that “Apple has seemingly evoked such a strong sense of customer loyalty that their buyers get a little crazy when a new product is released.”

You might think that the “cult of Apple” is an exaggeration, but neuroscientists would disagree.

In a study comparing the MRIs of Apple fans and individuals who self-identify as “very religious”, it was found that Apple and religion light up the same part of the brain. In other words, Apple causes a similar response in Apple fans as religion does in religious individuals.

Given that Apple is one of the most successful and well-known brands in the world, we can conclude that mass enthusiasm and fanaticism applies as much to consumerism as propaganda.

How Is This Relevant To Modern Marketing?

Propaganda and marketing can’t be separated (as much as many would like to pretend they can be), because they are based on the same fundamental principles.

As Danielle Rowell put it in The Power of Ideas: A Political Social-Psychological Theory of Democracy, Political Development and Political Communication, “State propaganda models are tactical strategies that employ enemy demonization techniques. The state promotes the idea that the threat (that is, tangible or intangible) is an evil aggressor”.

In Propaganda Techniques, Henry T. Conserva writes that “The oldest trick of the propagandist is to demonize and dehumanize the hated other or others and make the enemy a faceless object. Doing this makes it easier to hurt the opponent.”

We can see this in modern political campaigning too; Thomas Bodrick, chief technology officer of the UK Vote Leave campaign wrote, in Democracy for Sale, “I believe that a well-identified enemy is probably a 20% kicker to your vote”.

Don’t worry. We aren’t advocating for “demonization”, “dehumanization”, or setting up your competitor as an “evil aggressor”. This isn’t Game of Thrones. Although it would be pretty cool if it were. But what these statements do prove is that establishing an enemy isn’t just a part of conditioning, but the bedrock of it.

Britannica defines propaganda as follows:

Propaganda is the more or less systematic effort to manipulate other people’s beliefs, attitudes, or actions by means of symbols (words, gestures, banners, monuments, music, clothing, insignia, hairstyles, designs on coins and postage stamps, and so forth). Deliberateness and a relatively heavy emphasis on manipulation distinguish propaganda from casual conversation or the free and easy exchange of ideas. Propagandists have a specified goal or set of goals. To achieve these, they deliberately select facts, arguments, and displays of symbols and present them in ways they think will have the most effect.

Sound familiar?

Marketers also have a specific goal or set of goals in mind. They too select facts, arguments and displays of symbols. And they present them in such a way as to maximise their effect on consumers. Slogans, logos, banners, gestures, and merchandise are a brand’s weapons of choice, not so far flung from the weapons of propagandists.

The line between branding and propaganda is a very fine one, demonstrating that the definition of an enemy in political and marketing campaigns is by no means new. Rather, it’s a proven method grounded in our earliest examples of mass human persuasion.

Enemy-centric marketing works.

This isn’t some fad or marketing trend with a short shelf-life. This is a long-established tactic, and to overlook its history would be to diminish our understanding of it.

How To Define An Enemy For Your Business

It is crucial to note, of course, that the enemy defined by marketing campaigns doesn’t necessarily need to be an individual or even a competitor. The enemy could be, for example, a characteristic or a behaviour, as you’ll discover when we analyse enemy-centric marketing campaign examples later in this article.

But first, let’s break down the fundamentals of defining an enemy for your brand. How to choose your enemy, and correctly frame them, is an important process that requires consideration.

The following questions will help you select the most appropriate and powerful enemy for your brand. In addition, they’ll give you a sense of direction when it comes to creating an enemy-centric narrative.

- Who are your customers?

- Does your ideal customer identify with a specific group or value? If so, what?

- Does the problem your business is trying to solve align with this specific group or value?

- If not, how can you refine your branding to facilitate alignment with this specific group or value?

Here’s an example of how you might leverage the answers to these questions to define and frame your enemy.

Beyond Meat

Beyond Meat is a company providing alternative meat products.

- Their customers are vegetarian or vegan individuals.

- These customers are likely to identify strongly with the vegetarian movement, animal rights, and other vegetarians or vegans.

- The problem this business is trying to solve (meat consumption) is aligns perfectly with this specific group and their values.

With this in mind, Beyond Meat has a natural enemy in the meat industry and meat consumption. This is an enemy they emphasise in their branding. Their very name, Beyond Meat, implies this opposition.

But what about businesses that don’t have such an obvious enemy?

But what about businesses that don’t have such an obvious enemy?

Apple

Apple is a great example of a company that has carefully, purposefully, and strategically devised an enemy for their brand.

- Their customers are young individuals with a reasonable disposable income and willing to pay a premium for the latest technology.

- Their customers are likely to identify with individuals for whom Android and PCs were not satisfactory.

- The problem Apple is trying to solve (providing high-quality electronics) is not especially unique and does not align with their customers’ identification or values. This is because Apple customers have plenty of alternative sources of high-quality electronics. Because of this, low-quality electronics is not a sufficiently motivating enemy.

To resolve this issue, Apple devised an enemy-centric strategy that branded PCs as outdated, unintuitive, and generally “uncool”. In contrast, they branded themselves as young, intuitive, and fun.

In their Mac vs. PC ads, PCs are represented by a middle-aged man in an old-fashioned suit. While the Mac is represented by a young, fashionable man.

This series of adverts has contributed to Apple’s very successful oppositional marketing strategy. This strategy has involved them establishing themselves as a binary alternative to Windows and Android. By defining an enemy for their brand, Apple has positioned themselves successfully.

Enemy-Centric Marketing Campaign Examples To Inspire You

Defining an enemy isn’t the be all and end all of devising a successful marketing campaign. In fact, enemy-centric marketing is at its best in combination with other motivational forces. For example, the ego, a sense of belonging, and personal identification—to name just a few.

Outlined below are examples of marketing campaigns and brands that have actively defined an enemy in their marketing. We will explore whether this has been achieved implicitly or explicitly, as well as considering the other motivational forces contributing to the success of each.

Hopefully these examples will show you just how varied enemy-centric marketing can be.

Ben & Jerry’s

Ben & Jerry’s, the popular ice cream brand, is well-known for being vocal about politics and social issues. They even released an ice cream flavour called “Save Our Swirled Now”. The product was a non-dairy ice cream to accompany their “Climate Justice Now” campaign.

Note that Ben & Jerry’s doesn’t emphasise the impact of climate change in this campaign, but focuses instead on justice. In doing so, they place the culpability of the perpetrators of climate change at the centre of the campaign. Their call to action is demanding, powerful, and incites feelings of righteous anger.

The “Climate Justice Now” slogan also functions on another level, using justice to polarise consumers and coerce them into defining themselves either as an advocate for justice or the perpetrator of the crime.

This Ben & Jerry’s example, however, isn’t without its flaws. As a brand known primarily for its dairy ice cream products, this particular “climate justice” campaign lacks the power of more pervasive enemy-centric branding, of which Beyond Meat is a good example.

7UP

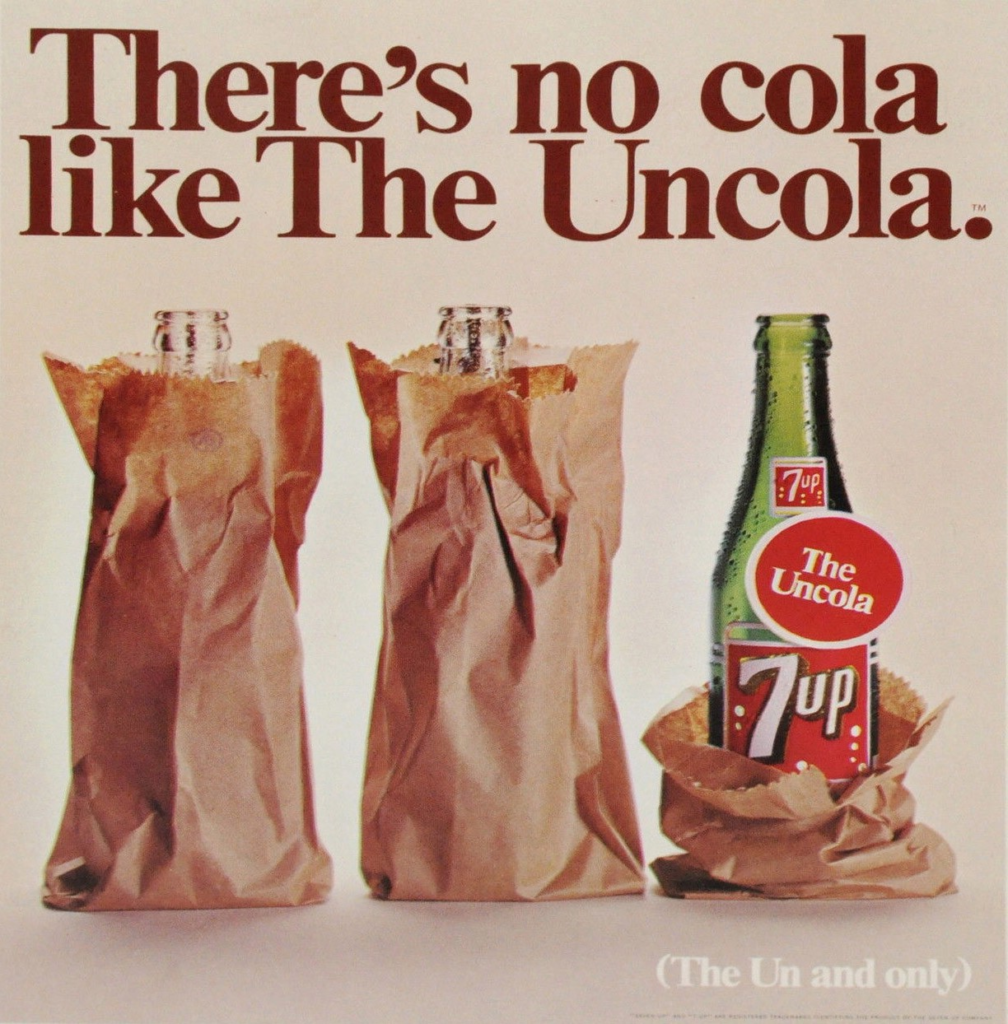

As Claire Payton writes in Uncola: Seven-Up, Counterculture and the Making of an American Brand, 7-UP used oppositional branding to establish their drink as “the ultimate oppositional drink: the ‘Uncola’. Rather than trying to play up the similarities the soda shared with its competitors, the new ads focused on its differences”.

7-UP used binary language, “Cola” and “Uncola” to stoke the fires of consumer loyalty. It became the antithesis of Cola to all those for whom Cola wasn’t quite hitting the spot. In this campaign, 7-UP defined themselves by their enemy (in this case, the competition—AKA, Cola); not by what they were, but what they were most certainly not.

As cited in Us Versus Them: Oppositional Brand Loyalty and the Cola Wars, “It is relatively well-established that consumers derive meaning and identity from what and how they consume”. But they also define themselves “in terms of what and how they do not consume”.

The article goes on to report that Hogg and Savolainen (1997) found that “consumers use brand choices to mark both their inclusion and exclusion from various lifestyles […] loyal users of a given brand may derive an important component of the meaning of the brand and their sense of self from their perceptions of competing brands, and may express their brand loyalty by playfully opposing those competing brands.”

This is called oppositional brand loyalty. A phenomenon that has been proven to impact us as consumers. One which was clearly utilised by 7-UP in its Uncola campaign.

By embracing Cola as their enemy, and clearly defining them in their marketing, they play into the oppositional brand loyalty phenomenon and take advantage of its effect.

Signal

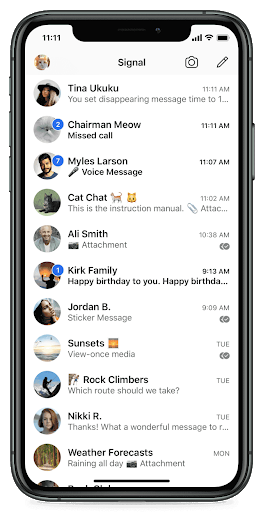

Signal is another example of a company leveraging oppositional marketing to define an explicit enemy. As part of their attack on Facebook’s privacy policy, they published a blog post that began, “Companies like Facebook aren’t building technology for you, they’re building technology for your data.”

In the case of Signal, the problem they are trying to solve is the lack of privacy on the vast majority of social media and messaging platforms. Their enemy is the sale of people’s data and privacy. And their main focus is to target Facebook specifically. They also criticise Instagram and WhatsApp, both of which Facebook own.

In their active criticism of Facebook, Signal defines themselves as an alternative. Like the 7UP Uncola campaign, Signal are defined by what they are not, rather than what they are. They are the anti-Facebook, and have successfully siphoned many of Facebook’s users.

Their product even mimics Facebook’s in style, using a very similar layout and colour scheme to Facebook Messenger, as seen below.

If anything, this aesthetic emphasises the similarities between Facebook and Signal, with one crucial difference; privacy. By stripping back all other differences and reducing their unique selling point to a single issue, Signal makes the choice between them and Facebook a simple one in what is a very purist and explicit form of enemy-centric branding.

The World Gym

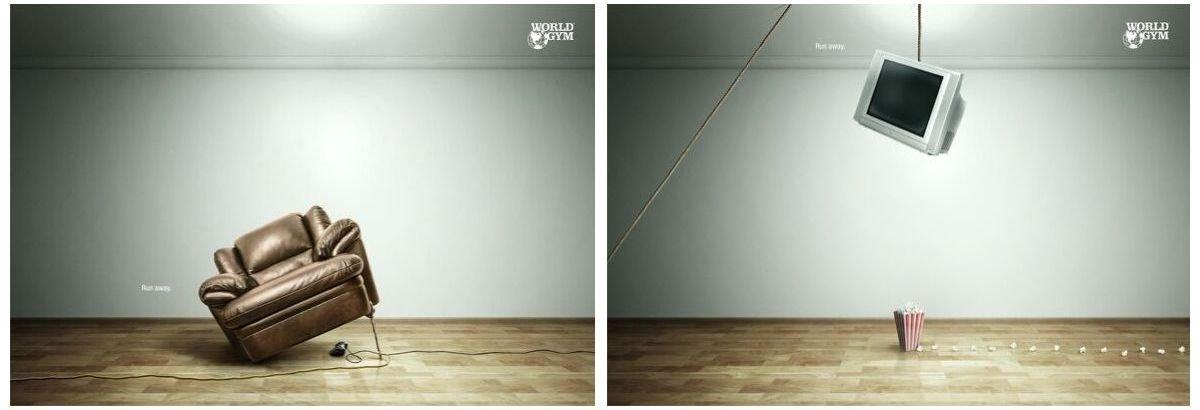

This World Gym advertisement uses the ego to establish an enemy future self. The experience of putting off going to the gym and falling into the trap of watching TV instead is a pretty familiar one for most.

Instead of depicting a man or woman with practically unattainable physiques, this advert poses a much simpler choice. Rather than show viewers what they could be if they hit the gym five times a week (a big stretch for most—pun intended), this advert shows viewers what they don’t want to be. Defining yourself as more than an individual who sits in watching TV is far simpler than becoming a bodybuilder; just get up, and go.

This advert plays on ego and even shame (albeit in a light-hearted way) to create an enemy of oneself. The enemy who once again passes on going to the gym.

Never underestimate the power of the ego in marketing. In an article titled “How to Reach Audiences and Influencers Through Their Ego”, it is reported that two out of five content sharing motivations are in service of the ego, according to The New York Times’ Psychology of Sharing study. Viewers shared content either to define themselves to others and to receive social validation or to achieve self-fulfillment and/or to get “credit” for sharing it.

Pairing appealing to your audience’s ego with defining an enemy can make for a strong enemy-centric marketing campaign, as proven by World Gym’s ad series.

Huel

Taking steps to cultivate a sense of belonging in your branding can create lifelong loyalty. And it is a very strong marketing strategy to boot. Agency In Motion discusses this phenomenon in their article titled The Psychology of Belonging: Why People Become Brand Fans.

“Consumers don’t see themselves so much as buying products but rather belonging to a larger movement. Such a movement aligns with an individual’s sense of self and drives him or her to evangelize the product on behalf of the company.”

Huel is an apt example of a modern brand that uses a sense of belonging to motivate loyalty. In Huel’s marketing, the enemy is diet food, diet shakes, and standard protein powders. They define themselves by what they are not, to attract a unique breed of customers that share their values; reducing waste, maximising health, and improving convenience without compromising nutrition.

On Huel’s homepage, you will see the following phrases:

- This isn’t diet-food. It’s food-food.

- Unlike diet shakes and simple protein powders, Huel is made with ingredients like…

Huel calls their users “Hueligans”. This is a clever branding tactic that defines users by their use of the product. This cultivates sense of belonging and serves to strengthen customer opposition to Huel’s enemies. By becoming Hueligans, they reject diet food and diet shakes. Hueligans even receive a free branded t-shirt with their first order, literally branding themselves as part of the Huel movement.

Why Is Defining An Enemy So Effective?

Whether in warfare, politics, storytelling, team sports, or consumerism, defining an enemy remains a powerful form of persuasion.

As the examples above have demonstrated, an enemy can be anything. It could be a competitor, a value, a behaviour, or a process. Enemy-centric marketing doesn’t need to be sleazy. It doesn’t need to be antagonistic.

But by defining your enemy and keeping them at the front of your mind when cultivating your brand, you can strengthen the impression you make on your audience. And, as a result, rally them behind you. After all, people can only be rallied when they have something to stand against.

That’s the true power of enemy-centric marketing.