The timeline is murky, but Scotland will gain independence one way or another, IndyRef2 or not.

It’s a bold claim, we know, and yet you won’t find any polls or cultural observations in this post.

We aren’t here to speculate on Scottish perceptions of Brexit, the handling of the pandemic, or any other socioeconomic circumstances that might have swayed the population towards voting for an independent Scotland.

No, we want to talk about marketing psychology.

You might be wondering why a small marketing consultancy based in East Anglia would be interested in writing an article predicting the outcome of an independence referendum in Scotland.

You might be thinking it’s none of our beeswax, and you might even be right.

We would argue that voter psychology and consumer psychology have a lot in common. We could even go so far as to say that they’re practically identical. It’s no coincidence, after all, that parties launch massive marketing campaigns in an effort to win over voters.

Campaigns claiming to save you money, improve your health, or make your life easier—that are perhaps uncomfortably similar to product advertisements promising miracle weight loss and business courses that will make you a millionaire overnight.

As marketers, we’re intrigued by how psychology affects consumer behaviour, and we think we can learn as much from voting patterns and political marketing campaigns as we can from non-political marketing campaigns.

With this in mind, we thought we’d conduct a little exercise, challenging ourselves to apply marketing psychology to the IndyRef2 campaign to see if we can predict the outcome.

Though we will speculate on how having an understanding of psychology can provide insights into why people vote the way they do, we would like to preface this article by saying that this isn’t an opinion piece, but is purely observational.

To be clear, we aren’t taking a position on whether or not Scotland should be independent. We are simply interested in the trends and patterns being leveraged to influence voters during political campaigning.

So, shall we get started?

Key Psychological Factors Impacting Voter Behaviours in IndyRef2

1. Mastery & Control

The desire for mastery and control are fascinating contributors to both how we vote and how we make purchases.

In a journal titled The Psychology of Risk Taking Behaviour, the authors provide support for the assumption that “personal control and mastery are emotionally and physiologically intrinsically rewarded”.

In other words, achieving personal control over a situation or behaviour is intrinsically valuable to us as individuals.

This deduction has plenty of support, including from a Harvard essay titled Changing the World and Changing the Self: A Two-Process Model of Perceived Control. In this essay, the author claims that “there is extensive evidence that people strongly value and are reluctant to relinquish the perception of control”.

It isn’t hard to identify this intrinsic need to exercise control over our environment in our voting behaviours. Take the Vote Leave campaign, for example, with its “Take Back Control” mantra. It’s an easy message to get behind with its overtones of mastering our own fates, empowerment of the individual, and the underdog taking on the establishment.

It isn’t hard to identify this intrinsic need to exercise control over our environment in our voting behaviours. Take the Vote Leave campaign, for example, with its “Take Back Control” mantra. It’s an easy message to get behind with its overtones of mastering our own fates, empowerment of the individual, and the underdog taking on the establishment.

‘Take Back Control’ is perhaps a far easier message to get behind than the elusive Vote Remain mantra, which (arguably) wasn’t as convincing, well-defined, or circulated as effectively.

As Dr. Tim Haughton of Birmingham University put it, “‘Take Back Control’ effectively combined not just a sense of a positive future albeit never defined or elaborated, but also suggested a sense of rightful ownership.”

A vote for an independent Scotland is equally tantalising, promising greater control and a similar sense of rightful ownership. Simply put, from a psychological standpoint the argument for freedom and mastery is far stronger and more appealing than the argument that things ought to remain as they are.

2. Self-Expression & Dissatisfaction

Why do we vote?

Though at first thought this question may seem like a simple one, psychologists have found it to be anything but. In an article published by the American Psychological Association titled ‘Why do we vote?’, the author points out that voting on the basis of “making a difference” seems to be a somewhat irrational notion.

The writer, Christopher Munsey, notes that the chances of an individual’s vote making a difference among the millions of votes cast is almost zero. Indeed, the chance of one person’s vote being the deciding vote in an election is significantly less than the chance of that same person being hit by a car on their way to vote.

Despite us all having at least a vague awareness of the miniscule chances that our individual votes will make a difference to the outcome, we are quite happy to brave the big bad world everyday and face those same (if not greater) chances of being rendered roadkill.

One could conclude then that the act of voting hinges on a form of egocentrism. This is essentially a sense that if I as an individual vote, like-minded people will probably vote too. This is referred to by psychologists as “voter’s illusion”.

Voting can also be borne of a sense of responsibility and collectivism; after all, a common sentiment expressed to people who abstain from voting on the grounds of its futility is, “but if everyone thought that way…”.

And then there’s self-expression, a crucial recognition of our own individual influence, which harks back to our intrinsic desire for personal control and mastery. It’s safe to say that self-expression plays at least some part in our voting behaviours, but what does this mean for IndyRef2?

Well, researchers have noted that humans spend far more time analysing bad experiences than good experiences. This is an evolutionary mechanism designed to keep us vigilant against threats.

You’re probably familiar with this experience; from a modern perspective, people are far more likely to express dissatisfaction at having lost £100 than they are satisfaction at having gained £100. The loss is more newsworthy than a gain of identical value.

You’re probably familiar with this experience; from a modern perspective, people are far more likely to express dissatisfaction at having lost £100 than they are satisfaction at having gained £100. The loss is more newsworthy than a gain of identical value.

Anyone who reads the news in any form will know this to be true; we’re more interested in observing the things that go wrong than the things that go right. This evolutionary fixation on the negative also applies to consumer habits—specifically, to product and service reviews.

According to a survey conducted by Review Trackers, “A consumer is 21 percent more likely to leave a review after a negative experience than a positive one.”

So, we can deduce from this finding that people are generally more likely to express dissatisfaction than satisfaction. If voting is a form of self-expression, then a campaign with a focal point of dissatisfaction (in this case, dissatisfaction with Westminster governance in Scotland) should in theory pack a greater punch than a campaign emphasising the positives of remaining in the union.

On this basis, you could also argue that voter turnout among independence-backers is likely to be higher than turnout among union-backers. Roch Dunin-Wasowicz in an article published on LSE’s website points out that the turnout of voters who supported leave in the Brexit referendum was higher than the turnout of voters who supported remain. Dunin-Wasowicz writes that “according to the first post-referendum poll (Ipsos/Newsnight, 29th June), those who did not vote were, by a ratio of 2:1, Remain supporters.”

This could be in part because people are, as psychologists have found, more likely to be motivated by expressions of dissatisfaction (i.e., dissatisfaction with EU influence) than satisfaction (i.e., satisfaction with being part of the EU).

Willingness to express dissatisfaction seems to be stronger when the source of the dissatisfaction is external or “other”. In the case of IndyRef2, Westminster.

3. Optimism vs. Pessimism

In 2009, Science Daily reported that studies had shown humans to be optimistic by nature. This finding should, in theory, mean that provided human optimism isn’t counteracted by certain factors (such as poor experiences), it should thrive under the right conditions.

“What makes IndyRef2 the right conditions?”, I hear you ask.

It has been argued that the primary obstacle to Scottish independence is uncertainty and fear of the unknown. In this Mashable article by Colin Daileda, the top two “cons” of Scottish independence are both uncertainty-centric. The first is uncertainty regarding currency and the second is uncertainty regarding financial markets in the UK.

Optimism is the combatant of uncertainty and, as we have already discovered, humans are by nature optimistic. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that optimism always wins out. Fear of change does, after all, exercise a significant amount of power over us as a species.

In politics, there are countless factors that can put a dent in voter optimism, such as evidence of poor leadership and recent party failings.

Given that the SNP party has been governing in Scotland for 13 years and that they’ve had recent success with the handling of the pandemic (74% of Scots think the Holyrood-based institution is doing well), it seems like conditions for optimism are pretty decent right now; this puts the SNP on good footing for a successful independence campaign.

When dissatisfaction and optimism meet, politicians are presented with a unique opportunity to pose voters with a choice; choose change or remain the same. IndyRef2 poses that choice to the people for the second time. With the right campaign, change sure does start to look tempting.

There is no better example of the strength of optimism than the National Lottery. After all, there are few circumstances that demonstrate greater optimism than buying a lottery ticket, with the odds of winning being roughly 1 in 45 million.

And yet at least 50% of the overall population buy tickets more than once a month, and on average they buy a minimum of 3 tickets each week. That means that despite losing time and time again, a significant proportion of players continue to buy tickets.

Here’s a National Lottery ad that really plays on the human predisposition towards optimism:

4. The Underdog Effect

In a paper titled The Underdog Effect: The Marketing of Disadvantage and Determination through Brand Biography, the authors identify what they call “The Underdog Effect”. This effect entails a brand (or in this case a campaign) using the impression of external disadvantage, humble origins, and a determined struggle against the odds to impact consumer (or voter) decisions. The underdog narrative has been known to increase buyer intentions and brand loyalty in consumer settings.

The paper argues that the underdog biography is effective because individuals identify positively with the underdog, seeing themselves perhaps as a similarly small cog in a big wheel. This experience of insignificance is especially prevalent in politics, where our single vote among millions has an almost non-existent impact on political outcomes; this can be used to the advantage of the pro-independence campaign in Scotland.

The paper argues that the underdog biography is effective because individuals identify positively with the underdog, seeing themselves perhaps as a similarly small cog in a big wheel. This experience of insignificance is especially prevalent in politics, where our single vote among millions has an almost non-existent impact on political outcomes; this can be used to the advantage of the pro-independence campaign in Scotland.

Having lost the vote in 2014, IndyRef2’s underdog case is ever-stronger, infused with an air of passion and determination that accompanies its long, continued struggle towards success.

The underdog vs. the establishment is an effective narrative, and one that the SNP are rightly making the most of in their campaign. Here are a couple of quotes from Nicola Sturgeon on Scottish independence that play into the underdog narrative:

“With all of our assets and talents, Scotland should be a thriving and driving force within Europe. Instead, we face being forced to the margins – sidelined within a UK that is, itself, increasingly sidelined on the international stage. Independence, by contrast, would allow us to protect our place in Europe.”

“Scotland’s 62% vote to remain in the EU counted for nothing. Far from being an equal partner at Westminster, Scotland’s voice is listened to only if it chimes with that of the UK majority; if it does not, we are outvoted and ignored.”

Having been broadly disappointed by the Brexit vote, it wouldn’t be much of a stretch to assume that the underdog vs. the establishment sentiment is stronger than ever in Scotland—which bodes very well indeed for the pro-independence campaign.

5. Personal Identification

In The Psychology of Voting, the author Jon A. Krosnick (Professor of Psychology and Political Science at Ohio State University) claims that “the single most powerful predictor of a person’s vote choice is his or her political party identification”.

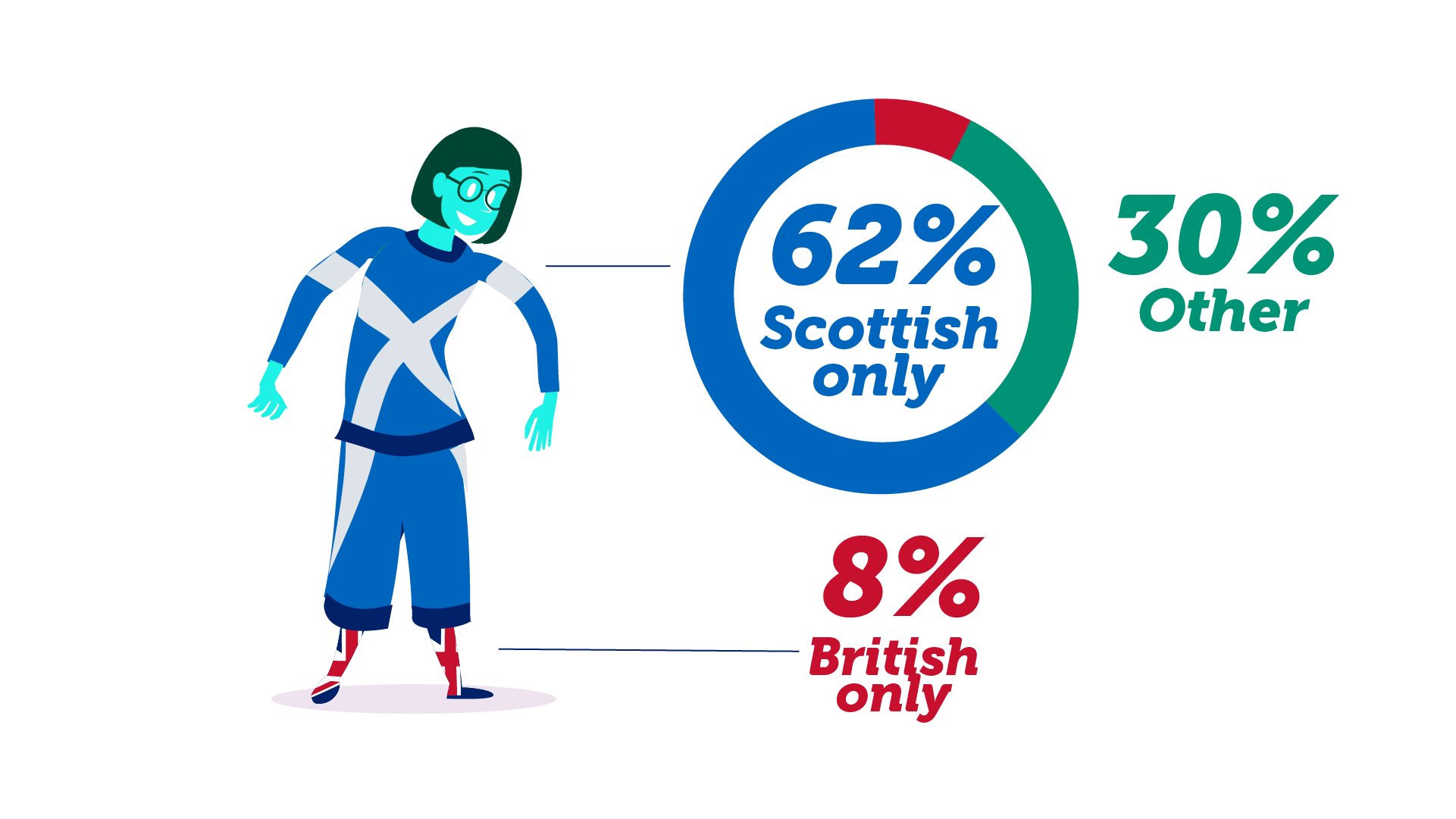

But research has shown that it is not only political party identification that drives votes, but national identity. The Brexit vote is the most obvious example of this. An article in Science Direct reports that “U.K. residents who believed that their English or British national identity was more causally central were more likely to support the U.K. leaving the European Union (Brexit) than those who believed the same identities were more causally peripheral.”

In other words, individuals who believed their English or British national identity was fundamental to their self-conception were far more likely to vote leave. It is no surprise then that the pro-independence campaign has always emphasised the Scottish identity of the people of Scotland.

In the 2011 Scotland Census, 62% of the total population stated their identity to be ‘Scottish only’, 18% stated their identity to be ‘Scottish and British identities only’, and just 8% chose ‘British identity only’. And of course, it is the Scottish National Party (a party name that speaks for itself) that has enjoyed power for an impressive 13 years. These facts speak to the Scottish public’s strong affiliation with their Scottish national identity.

In the 2011 Scotland Census, 62% of the total population stated their identity to be ‘Scottish only’, 18% stated their identity to be ‘Scottish and British identities only’, and just 8% chose ‘British identity only’. And of course, it is the Scottish National Party (a party name that speaks for itself) that has enjoyed power for an impressive 13 years. These facts speak to the Scottish public’s strong affiliation with their Scottish national identity.

Given that the majority identify strongly as Scottish, and Scottish only—and given the correlation between national identity and voting patterns as demonstrated by the Brexit vote—the pro-independence campaign are working with some pretty ideal conditions.

By leveraging national identity effectively in their campaign, as the vote leave campaign did, we would argue that they stand a more than decent chance of winning the vote—particularly when combined with the other factors listed in this article.

As David McCrone put it in an opinion piece published in the Centre on Constitutional Change, “Scotland got a UK government it did not vote for more than three-quarters of the period between 1945 and 2019, but England, very rarely (between 1964-66, and 1974-79). It might seem ‘obvious’ that electors in Scotland have become far more ‘Scottish’ and less ‘British’ since 1945, and that this has accounted for growing political divergence between Scotland and England.”

The conditions are right; they just have to make the most of them.

People are regularly exposed to campaigns that play on national identity and other personal identifications. Take tea as an example. Tetley tea, to be specific, who launched a “Best of British” campaign in 2016.

This ad campaign focuses on Britishness, British history, prominent British figures like Churchill, and our national identity as… tea drinkers? Yes, seriously. And it seriously works too.

An Independent Scotland is on the Horizon

So, to summarise, we have the attractiveness of an opportunity to exercise mastery and control, the contribution of the underdog effect, the desire to express dissatisfaction, the human predisposition to optimism, and the powerful temptation to reaffirm one’s identity; all of which accumulates into a very, very strong case for Scottish independence.

But wait, why then did Scotland vote “no” in 2014?

You might be wondering, if psychology is so deterministic, why the heck wasn’t the independence vote won in 2014?

A very good question.

The simple answer to this wonderance is that psychology isn’t deterministic. Though we can discuss human psychology until the cows come home, no one human is the same as another and there are a myriad of factors that contribute to the way we vote and buy. Some of these factors will be more important to certain individuals than they are to others.

Psychology is a lens through which we can view voting and buying behaviours—it’s useful and can be leveraged to the advantage of marketers and politicians alike.

But voting behaviour remains subject to socioeconomic circumstances, which we haven’t fully explored in this article. Scotland, and Britain as a whole, are caught in the midst of a pandemic, Brexit, and divisive austerity policies—all of which have radically and unpredictably altered the political landscape in this Celtic nation.

Ultimately, there is no absolute psychological formula that allows us to accurately predict the way people will vote or buy.

But there are patterns; patterns that political parties and marketers are getting better and better at using to inform their campaigns.